Background

On 15 April, the Sudanese Army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) were reported to have begun fighting throughout Sudan. Armed clashes have been reported in Khartoum, Merowe (Marawi), Nyala, Port Sudan, Zelengi, El Fasher, Omdurman, El Obeid, Damazine, Gedaref, Blue Nile state, Kassala and North Darfur, Central Darfur and West Darfur. In addition to rocket and mortar fire, mechanised tank as well as heavy artillery use has also been reported in the nationwide armed clashes over 15-21 April. Three separate humanitarian ceasefires on 18-20 April each failed to take hold. The Sudanese Army has confirmed that it has launched airstrikes against RSF positions over 15-21 April; sites in Khartoum, Merowe, Port Sudan and Omdurman have reportedly been targeted. Details are still emerging, and the security situation in Sudan remains fluid and subject to rapid change.

Aviation Impact

The fighting has also impacted civilian aviation on the ground; many of Sudan's airports are co-located with military airbases. Vehicle checkpoints, terminal facilities, hangars, fuel depots and the runway at Khartoum International Airport (HSSK/KRT) reportedly sustained damage due to artillery shelling and armed clashes over 15-21 April. As of 21 April, over 20 military and civilian aircraft on the ground at the facility, including at least three commercial passenger airliners, were heavily damaged and/or destroyed due to the fighting. Of note, on 19 April, the Egyptian military conducted four evacuation flights to/from Khartoum’s Wadi Seidna Air Base (HSWS) and Dongola Airport (HSDN/DOG) in northern Sudan.

In addition to Khartoum International Airport, armed clashes have been reported at the following airports/airbases in Sudan at various points over 15-20 April: Merowe (HSMN/MWE), Port Sudan (HSSP/PZU), El Obeid (HSOB/EBD), El Fasher (HSFS/ELF), Geneina (HSGN/EGN), Nyala (HSNN/UYL) and Jabal Awliya. It remains unclear at this time which forces – either the Sudanese Army or RSF – control these airports/airbases. Commercial satellite imagery, social media exploitation and traditional news outlet reporting from 15-20 April indicates that at least 15 military and civilian aircraft and helicopters on the ground at El Obeid and Merowe airports as well as Jabal Awliya Air Base have been heavily damaged and/or destroyed due to the fighting. In addition, damage to the runways, fuel depots and facilities at the airports in Merowe and Port Sudan have occurred.

In this edition of the Downlink we examine fairly widespread destruction at Khartoum International Airport in Sudan, with multiple aircraft — include two IL-76s, a 737, an A330 and a turboprop aircraft —totally destroyed. pic.twitter.com/LCcEBXv1yG

— The War Zone (@thewarzonewire) April 16, 2023

On 16-20 April, the RSF claimed it had shot down five combat aircraft, three helicopters and a drone operated by the Sudanese Army over Khartoum and Omdurman via employment of air-defence weapons of unspecified type/variant; however, this has yet to be independently verified. In addition, RSF air-defence units reportedly engaged Sudanese Army air assets over Omdurman, Khartoum and Merowe over 16-21 April.

On 16 April, a NOTAM was issued for FIR Khartoum (HSSS) indicating that, for security reasons, no air navigation service (ANS) is available for the airspace over Sudan or for flights in South Sudanese airspace above FL245 within FIR Juba (HJJJ) (HSSS A0066/23). As such, all airports in Sudan are effectively not operating, and the FIR Khartoum (HSSS) airspace is closed.

On 21 April, the UK, France and Germany all issued NOTAMs regarding the conflict activity in Sudan:

- The UK recommends operators do not enter FIR Khartoum (HSSS) within the territory and airspace of Sudan, due to the potential risk from anti-aircraft weaponry and heightened military activity (EGTT/EGPX/EGGX V0010/23, valid through 19 July).

- France requests operators not to penetrate the part of FIR Khartoum (HSSS) over Sudan’s territory, and not to identify Sudanese airports as alternates (LFBB/LFFF/LFEE/LFMM/LFRR F0687/23, valid through 31 May).

- Germany prohibits its carriers from entering FIR/UIR Khartoum (HSSS) due to the risk from anti-aviation weaponry, military operations and armed conflict (EDGG/EDWW/EDMM B0264/23, valid through 21 July).

Do not act based on unverified information; however, ensure emergency response and communications plans are up to date to facilitate continuity during times of crisis. Aviation operators should monitor airport/airspace-specific notices, bulletins, circulars, advisories, prohibitions and restrictions prior to departure to avoid flight schedule disruption.

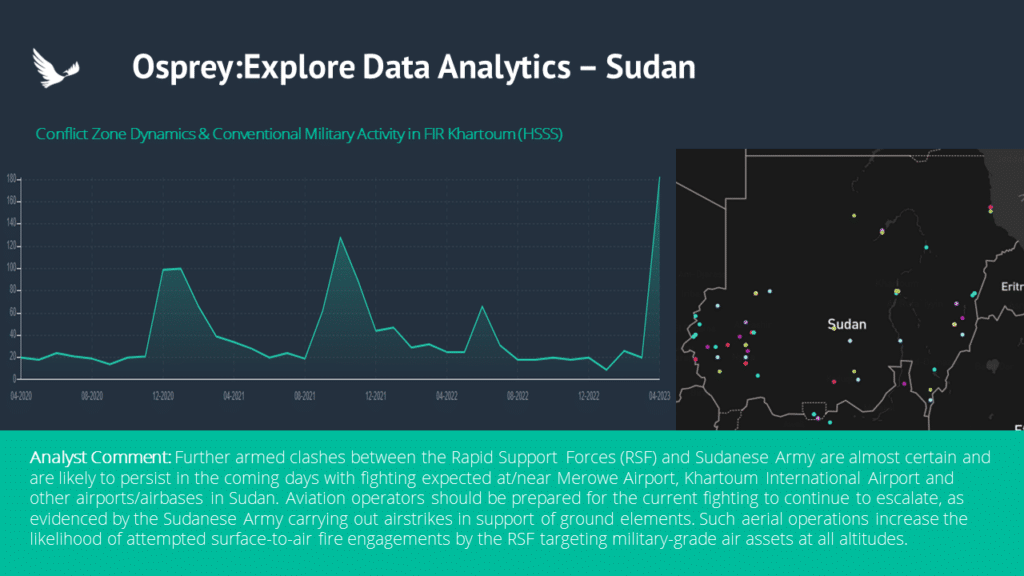

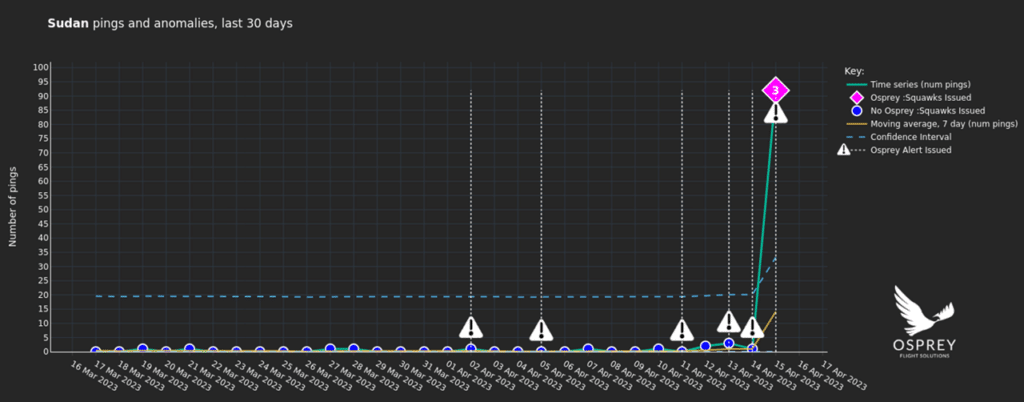

The power of risk monitoring

Prior to the outbreak of conflict on 15 April, Osprey had published over 16 updates on Sudan's ongoing unrest and tensions since April 2022, as well as multiple alerts on clashes between Ethiopian and Sudanese forces on their shared border. Additionally, on 13 April, we published an update regarding the increase in tensions in the country after news broke that the RSF had begun mobilising in northern Sudan near Merowe Airport. The information came through to Osprey Flight Solutions' analysis team through sources used to monitor human trafficking. This was due to the fact that the RSF released a statement that announced, in Arabic, that they were deploying in order to achieve security and stability, to combat human trafficking, illegal immigration, smuggling, drugs and transient crime, and to confront armed robbery gangs.

In our 13 April update, we highlighted to clients that operators should be prepared for continued tensions and the possibility of clashes between the Sudanese military and RSF nationwide in the coming days. This included highlighting the possibility that the tensions might escalate into clashes and prolonged fighting throughout the country in the coming days. Given the importance of aviation facilities in providing the Sudanese Army with air superiority over the RSF, airports - including Khartoum International Airport - were also highlighted as likely flash points between the rival forces.

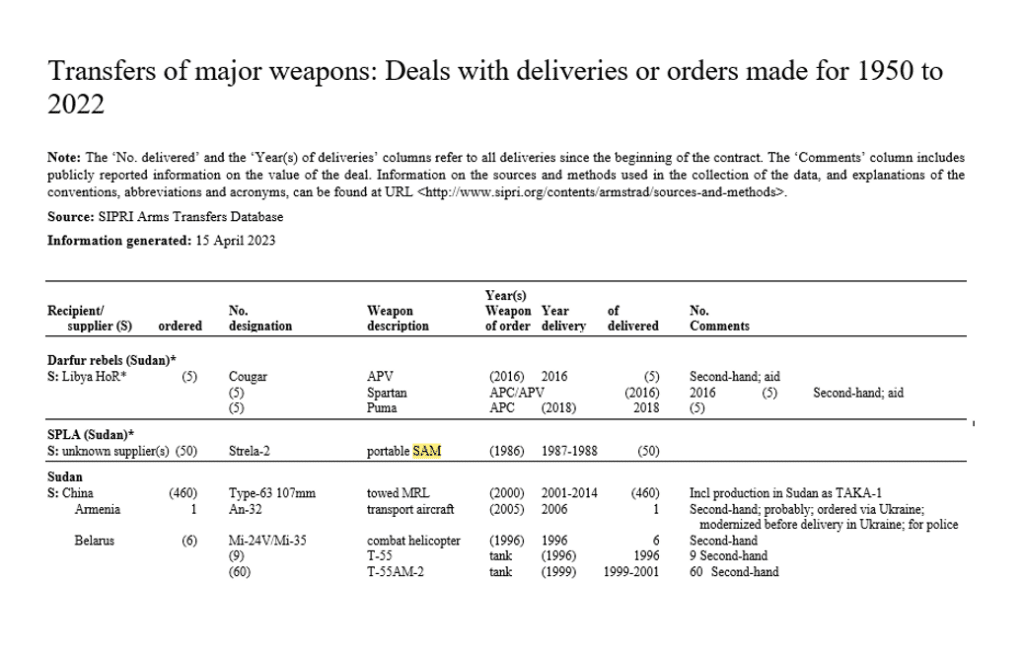

Analysis of Air & Air-Defence Capabilities

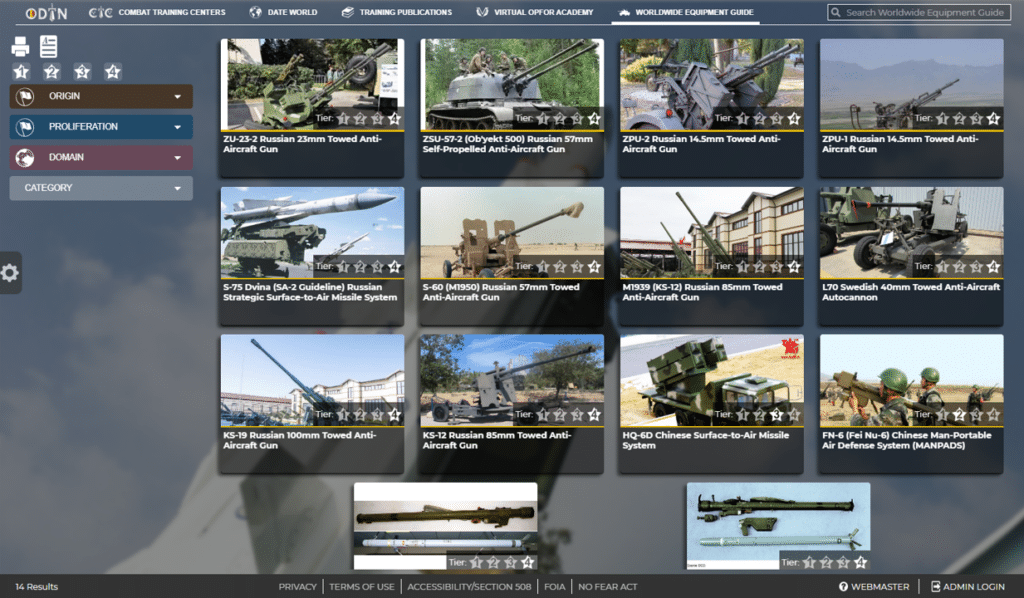

The fighting has already involved the deployment of air assets – the Sudanese Army has a small number of combat aircraft, helicopters and drones at its disposal, and the RSF may have access to a small number of helicopters and drones. Both the Sudanese Army and the RSF are in possession of light weapons, including low calibre 12.7mm/14.5mm/20mm/23mm anti-aircraft artillery (AAA), rocket-propelled grenades, unguided anti-tank weapons and anti-tank guided missiles, capable of engaging air assets below FL100. Both the Sudanese Army and RSF have procured man-portable air-defence systems (MANPADS) capable of engaging air assets below FL260.

The Sudanese Army possesses medium-calibre AAA capable of engaging air assets between FL100-FL260, including 37mm/40mm/57mm anti-aircraft guns. The Sudanese Army is also in possession of large-calibre AAA capable of engaging air assets at cruising altitudes, including M-1942 76mm (FL330) as well as KS-12 85mm (FL330) and KS-19 100mm (FL500) anti-aircraft cannons. Along these lines, the Sudanese Army has highly mobile Chinese-made FB-6A air-defence systems, which are capable up to FL260 and out to 6km (3.7 miles).

Not easy to see, but last week's exercise in Sudan featured the truck-mounted variant of China's FB-6A short-range air defence system pic.twitter.com/Uv8YJlrwlx

— Jeremy Binnie (@JeremyBinnie) December 13, 2016

Of most immediate concern, the Sudanese Army is known to be in possession of highly mobile conventional surface-to-air missile (SAM) systems. This includes the Russian-made 9K33 Osa (SA-8 GECKO), with the most capable variant of the SA-8 able to engage targets up to FL450 and out to 15km (9.3 miles). In addition, US Army reporting indicates that the Sudanese Army reportedly possesses Chinese-made HQ-6D conventional SAM systems, which are capable out to 18km (11 miles) and up to FL450.

Sudan armed forces 9K33 Osa (SA-8 Gecko) missile launch during the recent military Exercise 'Knight's Challenge' pic.twitter.com/98mJ9JGubu

— alex (@africaken1) January 24, 2017

The Sudanese Army also possesses Russian-made S-75 Dvina (SA-2 GUIDELINE) conventional SAM systems. However, the operational status of the SA-2s are unclarified due to their age and uncertainty surrounding Sudanese Army air-defence unit crew proficiency. The SA-2 has the capability to engage aircraft at altitudes up to FL820 and at ranges out to 28 miles (45 km).

Osprey is closely monitoring the situation for any changes to the conventional SAM system and large-calibre AAA orders of battle in Sudan, amid RSF attempts to take control of Sudanese Army bases. We no longer assess that all Sudanese Army conventional SAM systems are currently under the span of control of the state – which a specific concern that several SA-8s likely have been captured by the RSF. Osprey assesses that in the near term, the RSF could effectively operate SA-8s or other conventional SAM systems, if they are in fact now in their possession and fully intact, via external assistance. However, maintaining conventional SAM systems in the medium-to-long term would be a significant logistical hurdle for the RSF without significant external assistance.

#Sudan ??: Rapid Support Forces (#RSF) released a couple of videos from a military camp captured from Sudanese Armed Forces.

— War Noir (@war_noir) April 21, 2023

Seemingly three possible 9K33M2/M3 "Osa-AK(M)" short-range surface-to-air missile systems and 57mm AZP S-60 autocannons/anti-aircraft guns were captured. pic.twitter.com/ZeV5sklkp8

Outlook

Going forward, unless both the Sudanese Army and RSF adhere to any brokered ceasefire or one side gains a significant advantage quickly, fighting looks set to continue into the coming days. The Sudanese Army has reported a number of gains in recent days, including the recapturing of Merowe Airport, though an RSF presence is reported to remain in the nearby city. Despite this, control over Khartoum International Airport remains contested and both the Sudanese Army and RSF are intent on capturing the installation. Amid the armed clashes, indirect-fire attacks via rockets, mortars or artillery against airports and airbases within Sudan are likely in the days ahead, as such activity has continued daily since the start of the conflict.

Heavy fighting continues to be reported in Khartoum, with both sides fairly evenly matched amid the urban combat environment. The Sudanese Army has relied heavily on its air assets and continues to carry out airstrikes on RSF positions in the capital and across the country. Aerial operations increase the likelihood of attempted surface-to-air fire engagements by the RSF targeting military-grade air assets at all altitudes. While there are no indications at present that the RSF and/or Sudanese Army intend to kinetically target legal civil aviation flights, Osprey assesses that there is an significantly increased potential for miscalculation and/or misidentification at present over FIR Khartoum (HSSS) at all altitudes.

Rerouting of civil aviation overflights away from both FIR Khartoum (HSSS) and FIR Juba (HJJJ) is likely to persist in the near team amid the ongoing armed conflict in Sudan between the RSF and Sudanese Army. Operators should remain prepared for an ongoing loss of access to Sudanese and South Sudanese airspace for overflights of FIR Khartoum (HSSS) and FIR Juba (HJJJ) until a ceasefire is reached between the Sudanese Army and RSF, or until adequate ANS provision can be re-established by the authorities in Sudan.