In recent years, the trafficking of narcotics via illegal flight operations has been a persistent issue in Central America, and one that has seemingly been undeterred by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which has significantly disrupted commercial passenger flights over the past year. While some countries in the region have also witnessed a decline in the number of aircraft seized in connection with narcotics trafficking, media reporting, particularly in Guatemala, indicates that the pandemic has seen traffickers increasingly moving drug shipments by air, rather than maritime and land transport.

The following article will examine the prevalence of narcotics-trafficking flights in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and other factors that may have impacted the number of detected trafficking flights, including US military activity in the Caribbean Sea.

Narcotics-trafficking flights, which predominantly transport cocaine, usually arrive from South America, for example Colombia, Venezuela and Argentina, and aim to reach drug-trafficking organisations in Central America, ultimately Mexico, where the narcotics can be either smuggled via land transport to the United States (US) for distribution, trafficked to other regions, such as Europe, or distributed on local markets.

In early 2020, governments in the Central America region responded to the global COVID-19 pandemic by implementing travel restrictions. The extent of the restrictions varied, including in some instances the temporary closure of air, land and sea borders, and the imposition of strict social distancing measures, including temporary lockdowns, in efforts to prevent the spread of the virus. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the global aviation sector, including restrictions on travel, have resulted in significantly reduced commercial passenger flights. Globally, international passenger demand was 75.6% lower in 2020 compared to 2019, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA).

as border restrictions have been eased, narcotics-trafficking flights have reportedly increased

Significantly, increased border controls imposed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic have reportedly impacted the smuggling, mainly from Venezuela, of precursor chemicals required to manufacture cocaine. Subsequently, this is thought to have affected the production of cocaine in Colombia, regarded as a major exporter of narcotics, chiefly cocaine, according to a report published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in May 2020. These impacts on the production of narcotics have subsequently had a knock-on effect on narcotics trafficking in the Americas, including but not limited to trafficking via air transport. However, as border restrictions have been eased, narcotics-trafficking flights have reportedly increased, a phenomenon even recognised by Guatemala’s president.

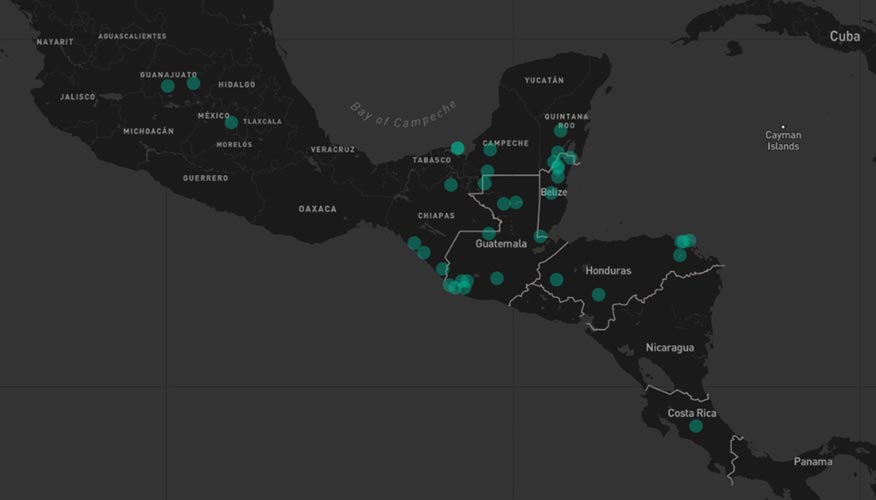

In the past year, multiple narcotics-trafficking flights have been detected in the area where Mexico, Belize and Guatemala converge. This largely encompasses the states of Quintana Roo, Campeche and Yucatan in Mexico, the Orange Walk District and Belize District in Belize and the Petén region in Guatemala. Several illegal flight operations suspected of narcotics-trafficking activity were detected in Quintana Roo alone during 2020. In a significant incident on 27 October, 1.5 tonnes of suspected cocaine were seized from an aircraft that had made an emergency landing at Chetumal International Airport (MMCM/CTM). The aircraft was reportedly detected after entering Mexican airspace with two other aircraft — which later departed Mexican airspace — from the direction of South America.

According to the US Department of State’s International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) 2021, between January and October 2020, Belize “documented 12 illicit aircraft” carrying varying quantities of cocaine (US Department of State, 2021, p. 96). Comparatively, in the 2020 edition of the INCSR report, it stated that during the same period in 2019, authorities seized seven aircraft suspected of trafficking narcotics, which had either been torched or abandoned, and several others were “successfully interdicted” (US Department of State, 2020, p. 101). However, these figures do not cover November and December of 2019 and 2020. In December 2019, the burnt remains of two aircraft were located in Corozal District, and in December 2020, a suspected narcotics-trafficking aircraft landed on a clandestine runway in Toledo District but was torched and abandoned by its occupants. As highlighted in both editions of the INCSR report, it is difficult to obtain reliable data on the successful landings of illicit aircraft on remote airstrips in Belize; however, the figures provided indicate that despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the detection of illicit flights increased in 2020.

In Guatemala, media reports quoting a spokesperson for the Armed Forces of Guatemala (ENG) stated that 39 aircraft suspected of trafficking narcotics landed in Guatemala in 2020. Comparatively, in 2019 the ENG located 54 aircraft. However, according to local media reports quoting figures provided by the National Civil Police (PNC) and Ministry of National Defence (MDN), over 84% of all cocaine seized in 2020 in Guatemala was transported by air — a huge increase compared to just 3.34% in 2019 and 4.12% in 2018, although the figures provided for 2020 cover only January through to 9 November.

This indicates that the use of aircraft to traffic narcotics has increased despite the impacts of the pandemic, such as border closures and increased controls. Significantly, transport via sea and land has declined considerably during this period. However, the total amount of cocaine seized in 2020 (up to 9 November) was only around half of the total seized in 2019.

The effectiveness of trafficking by aircraft has contributed to the lower overall figures for seizures, potentially more so than the impact of the pandemic.

The report also claims that in the majority of instances, authorities in Guatemala did not seize any narcotics from the illicit flights, indicating that traffickers were able to flee with the drugs. This also suggests that the effectiveness of trafficking by aircraft has contributed to the lower overall figures for seizures, potentially more so than the impact of the pandemic.

Notably, in the INCSR 2021, it is stated that in Guatemala in 2020, drug traffickers “increasingly used commercial executive jets” (US Department of State, 2021, p. 141), which have the ability to outperform ENG aircraft. Similarly, an official of the Comprehensive Air Surveillance System (SIVA) of the Mexican Air Force (FAM) was quoted in a report in July 2020 observing that traffickers are increasingly using business jets, which are quicker and have larger cargo capacities, as opposed to the traditional use of light aircraft.

In the majority of cases, aircraft suspected of trafficking narcotics land on clandestine airstrips. As such, the armed forces in Central American countries have frequently announced the destruction of detected airstrips to prevent their future use. For example, 37 landing areas were disabled by the Honduran Armed Forces (FFAA) in 2020, narrowly surpassing the number disabled in 2019 (36). The majority of the clandestine landing areas discovered in Honduras are located in Gracias a Dios department; this includes La Mosquitia region, which extends into Nicaragua — a popular corridor for trafficking narcotics between South and Central America and North America. Comparatively, in 2020, Mexico’s Secretariat of National Defence (SEDENA) recorded a 75% decline in the number of clandestine airstrips detected compared to the previous year, with 16 and 65 respectively. This decline has been in part attributed to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other Activity Affecting Narcotics-Trafficking Flights

Whilst the COVID-19 pandemic has evidently affected the frequency of narcotics-trafficking flights, other activity in the region has also had an impact. In April 2020, the US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) began “enhanced counternarcotics operations” in the eastern Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea and increased its presence of naval and coast guard vessels and air units, as well as US Air Force aircraft, to counter narcotics trafficking to the US, chiefly from Venezuela, as directed by former US President Donald Trump. As part of the counter-narcotics operations, the US received support from 22 other nations, including Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Panama in the Central America region.

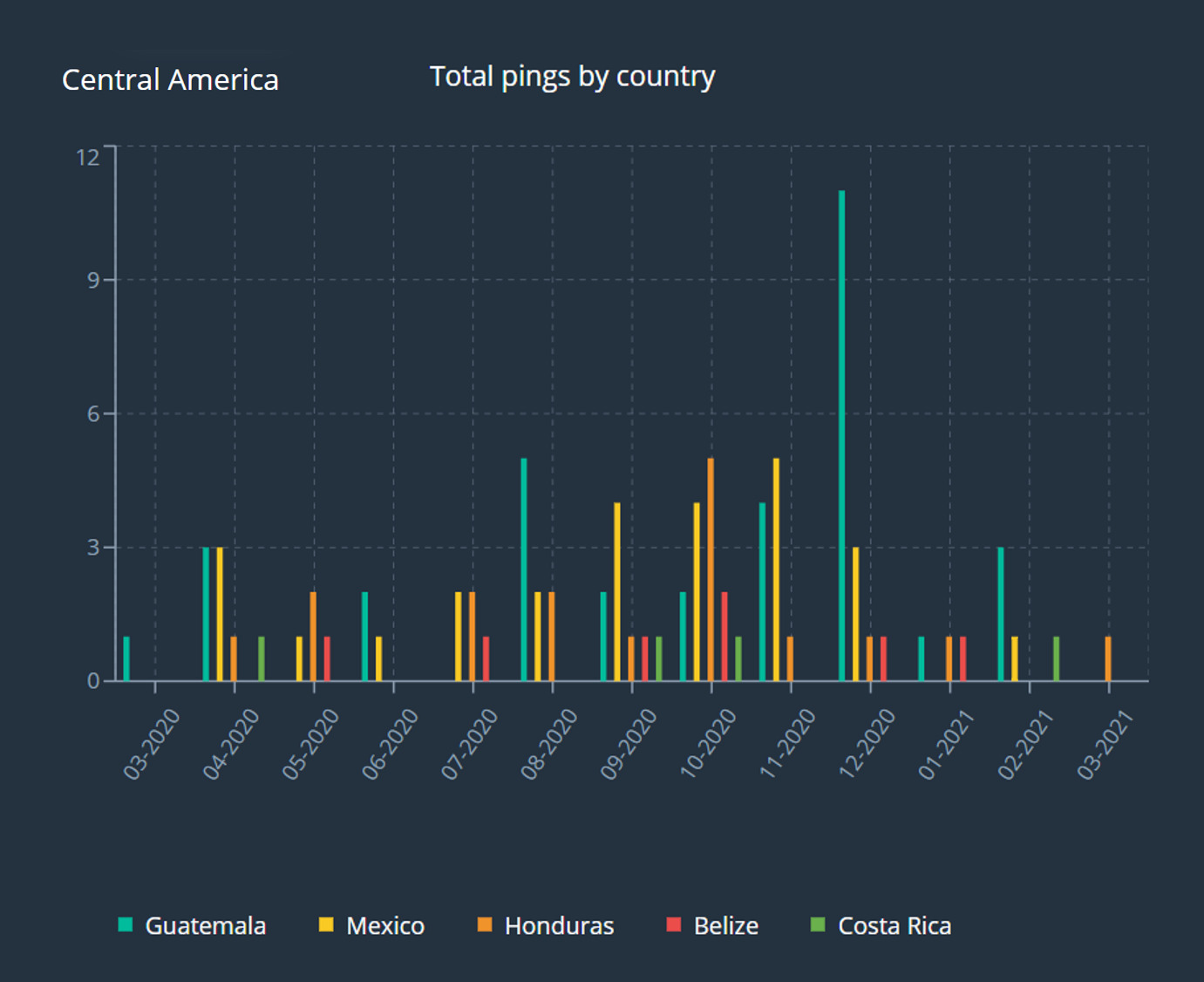

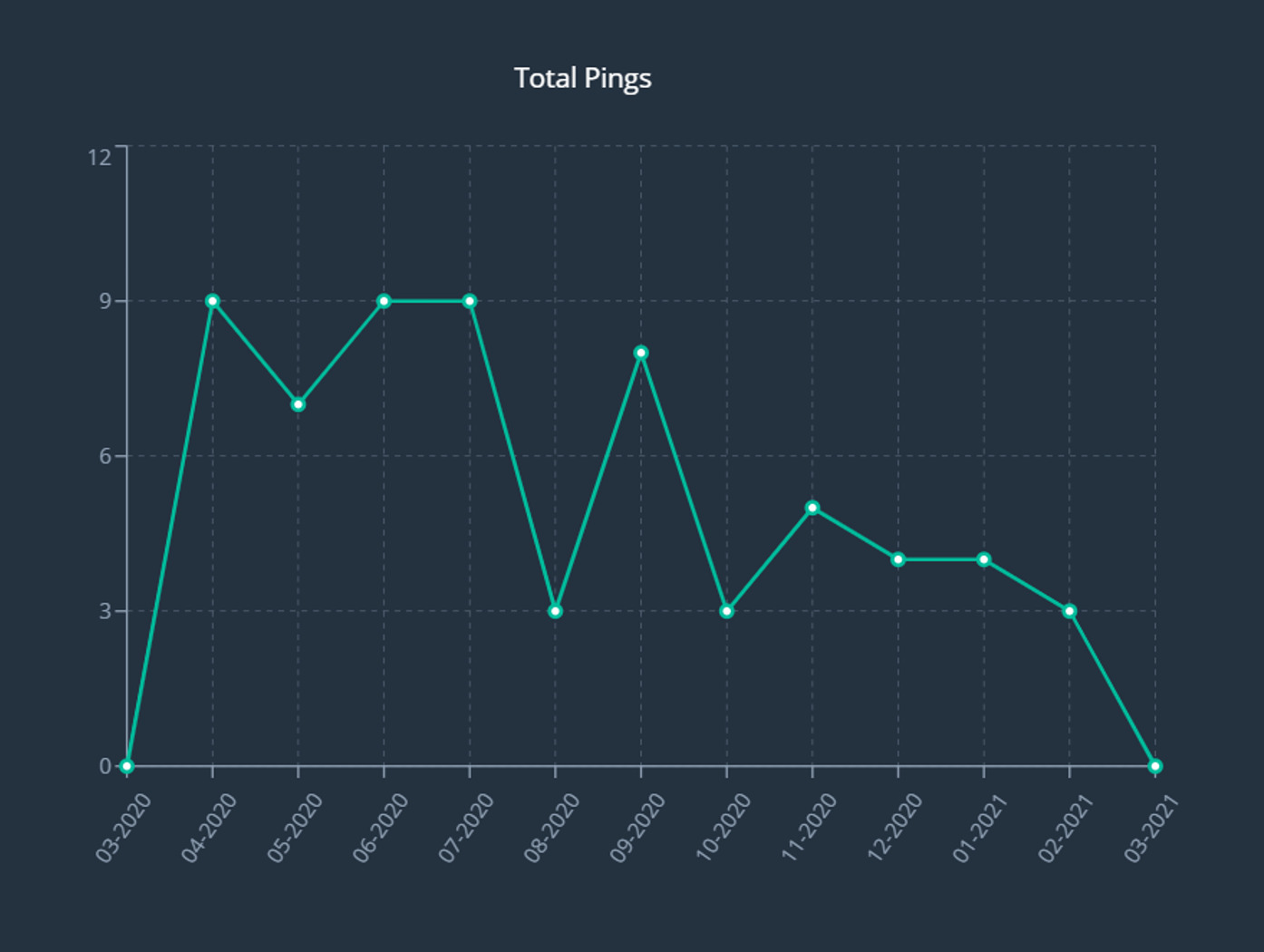

The Osprey:Explore chart below shows military air activity between March 2020 and March 2021, highlighting SOUTHCOM air activity in the Caribbean Sea beginning in April 2020. Since April, SOUTHCOM has reported significant narcotics seizures resulting from its operations.

As highlighted in the INCSR 2020, the “growing effectiveness and capacity” of the Guatemalan Naval Special Forces (FEN) has seemingly pushed narcotics traffickers away from Guatemala’s coasts; however, this in turn has driven traffickers to increasingly use “illicit air deliveries” to introduce drugs into the country (US Department of State, 2020, p. 149). The shift in trafficking mode from maritime to air transport was reiterated in the 2021 edition of the INCSR report. Additionally, during a press conference in August, Rear Admiral Andrew Tiongson, the director of operations of US SOUTHCOM, stated that in response to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic — including the closure of maritime ports — and US military operations, traffickers from Guatemala are increasingly using air transport to move drug shipments.

Furthermore, throughout President Trump’s term, pressure was placed on the Mexican government to reduce drug trafficking across the US-Mexico border. Therefore, the Mexican government tightened its land border with Guatemala, also in part to prevent the movement of migrant caravans, which President Trump also pushed to be halted. It has therefore been theorised that increased border controls have also contributed to the increase in narcotics-trafficking flights.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Illegal flights remain a serious concern from an aviation security and safety perspective; given the clandestine nature of narcotics-trafficking flights, pilots involved in such activity are unlikely to use transponders, maintain ATC radio contact or file flight plans. While military counter-narcotics air activity continues across the region, Honduras has now passed the Airspace Sovereignty Protection Act (2020), which no longer permits the Honduran Armed Forces (FFAA) to shoot down illegal flights — this is only authorised in cases of “legitimate defence”. However, while legal civil aviation flights are unlikely to be directly targeted via kinetic engagements, there remains a latent but credible risk of misidentification by Honduran military air assets. This emphasises the importance of operators ensuring that flight plans are correctly filed, as well as obtaining proper special approvals for flight operations to sensitive locations and relevant overflight permits prior to departure.

Other countries in the region – El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama – have also been impacted by narcotics-trafficking flights, although to a far lesser extent than those discussed above. However, in recent years, Costa Rica has become gradually more implicated in the trafficking of cocaine and is being increasingly used as a narcotics transshipment point in Central America. As such, on 21 September, a law was ratified allowing the Public Forces of Costa Rica, specifically the Air Vigilance Service, to enter private property to identify and then “disable, demolish and destroy” clandestine airstrips.

As demonstrated by Osprey’s analysis, narcotics-trafficking activity has increased since COVID-19 restrictions were eased, which would indicate that this activity will increase as restrictions are further relaxed.

Narcotics-trafficking flights have continued despite COVID-19-related restrictions on air travel; however, the effects of the pandemic — largely border closures — have, to an extent, disrupted this activity. As demonstrated by Osprey’s analysis, narcotics-trafficking activity has increased since COVID-19 restrictions were eased, which would indicate that this activity will increase as restrictions are further relaxed. However, the easing of restrictions may also see traffickers return to other forms of trafficking traditionally used, such as maritime and land transport, which have been affected by border and port closures. Additionally, the resumption of commercial passenger flights, albeit on a reduced level, has seen a resurgence in smuggling via passengers; however, significantly smaller volumes of drugs can be smuggled using this method.

Moreover, the impacts of other activity ongoing in the region, including efforts by the US and Central American governments to deter drug trafficking, are also likely to influence future trafficking trends. As noted above, SOUTHCOM operations in the Caribbean Sea have resulted in traffickers increasingly using air transport, as opposed to maritime. It should also be taken into consideration, as demonstrated in Guatemala, that authorities usually locate aircraft used for narcotics trafficking after they have been abandoned. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain how many narcotics-trafficking flights are able to deliver the narcotics and then depart a country’s airspace without being detected and intercepted. As such, the improved capability of traffickers to conduct narcotics-trafficking flights may result in an apparent decline in the activity, despite it persisting.