Background

In February 2020, the US and the Taliban signed an agreement aimed at ending the war in Afghanistan, though the extremist Islamic State Khorasan Province (IS-KP) violent non-state actor (VNSA) group is not a direct party to the pact. In January, the US announced it had reduced its military presence in Afghanistan to c.2,500 personnel. US military forces were to completely withdraw from Afghanistan by 1 May as part of the agreement with the Taliban; however, the US government pushed back its withdrawal date to 31 August. As part of the drawdown operations, the US deployed B-52 bombers to the Middle East and an aircraft carrier to the Arabian Sea to support military forces departing Afghanistan.

On 22 August, the US Department of Defense (DoD) activated the Civil Reserve Air Fleet, and aircraft from several US commercial airlines were requested to assist airlift operations after Afghans and Americans were transported out of Afghanistan from Kabul Airport to locations in third-party countries such as Qatar, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates and Germany. The US DoD specifically requested 18 commercial aircraft to facilitate ‘onward movement’ of evacuees: three each from American Airlines, Atlas Air, Delta and Omni; two from Hawaiian Airlines; and four from United. These aircraft were not required to operate to/from Kabul Airport.

Since 6 August, the Taliban have taken control of 33 of 34 provincial capitals in Afghanistan. On 15 August, the Taliban claimed control of Afghanistan and its fighters entered Kabul to occupy police stations and government buildings. As of 1930 UTC on 30 August, the US military confirmed that it had completed withdrawal operations from Afghanistan and the Taliban has claimed full control over Kabul Airport (OAKB/KBL).

Flight operations to and over Afghanistan now face severe operational constraints coupled with a dynamically evolving threat environment. This article will cover the following aspects of aviation operations to and over Afghanistan:

- Airports: Operational Factors

- Airspace: Operating Constraints

- Taliban: Military Equipment & Air Bases

- Threat: VNSA Groups in Afghanistan

- Threat: External Counterterrorism Concerns

Airports: Operational Factors

A NOTAM issued on 30 August states that Kabul Airport is uncontrolled and that no air traffic control (ATC) or airport services are available (OAKB A0022/21). Talks remain ongoing surrounding an enduring Turkish and Qatari government presence in Afghanistan aimed at keeping Kabul Airport operational after 31 August; however, no agreement has yet been publicly announced. Below are details of the proposed conditions:

- Turkey and Qatar will operate the airport in a consortium;

- Turkey will provide security through a private firm, whose staff will consist of former Turkish soldiers and police;

- Additional members of the Turkish special forces, operating in plainclothes to secure Turkish technical staff, will not leave the airport perimeter.

Despite the above, the Turkish Foreign Minister stated that inspection reports show runways, towers and terminals – including those in the civilian side of the airport – were damaged and needed to be repaired. In addition, recent reporting from commercial airlines has noted there is an absence of security checks and immigration staff on the civilian side at Kabul Airport.

The United Nations (UN) World Food Programme and World Health Organization are reportedly in the process of activating a humanitarian ‘air bridge’ in Afghanistan and flights to Kabul Airport and Mazar-i-Sharif Airport (OMAS/MZR) have occurred as part of this effort. In addition, at least one Qatari military flight and a civilian humanitarian flight reportedly occurred at Kandahar Airport (OAKN/KDH) in the past two weeks. Like Kabul, ATC services are reportedly unavailable at Kandahar and Mazar-i-Sharif airports at this time.

In addition, the Taliban control the following major airports: Herat (OAHR/HEA), Jalalabad (OAJL), Konduz (OAUZ/UND) and Farah (OAFR/FAH). These airports have been non-operational in recent weeks, and no civilian flight activity has been observed by Osprey. At the very least, commercial flights at each of the airports have been suspended indefinitely.

Analyst Comment

The presence of armed conflict within Afghanistan coupled with heightened levels of crime, social unrest and aviation infrastructure deficits pose logistical constraints to civilian flight operations within the country. In addition, the threat of militancy posed to aviation within Afghanistan is highlighted by recent attacks against airports and aircraft inflight. Afghanistan does not meet International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards for safety, and the security posture at airports in the country varies considerably. Security personnel are unlikely trained to the highest international standards, and staff responsible for safeguarding airport operations likely face severe difficulties in handling significant aviation-related safety or security events.

A Turkish and Qatari agreement with the Taliban for a presence after 31 August would likely aid in the provision of ATC service at Kabul Airport going forward, though this has yet to materialise. The NOTAM stating that Kabul Airport is now uncontrolled represents a significant safety-of-flight concern, and rerouting of flights away from the Afghan capital is now a definitive operational constraint. Operators should remain prepared for a loss of access to Kabul Airport for the foreseeable future.

Airspace: Operating Constraints

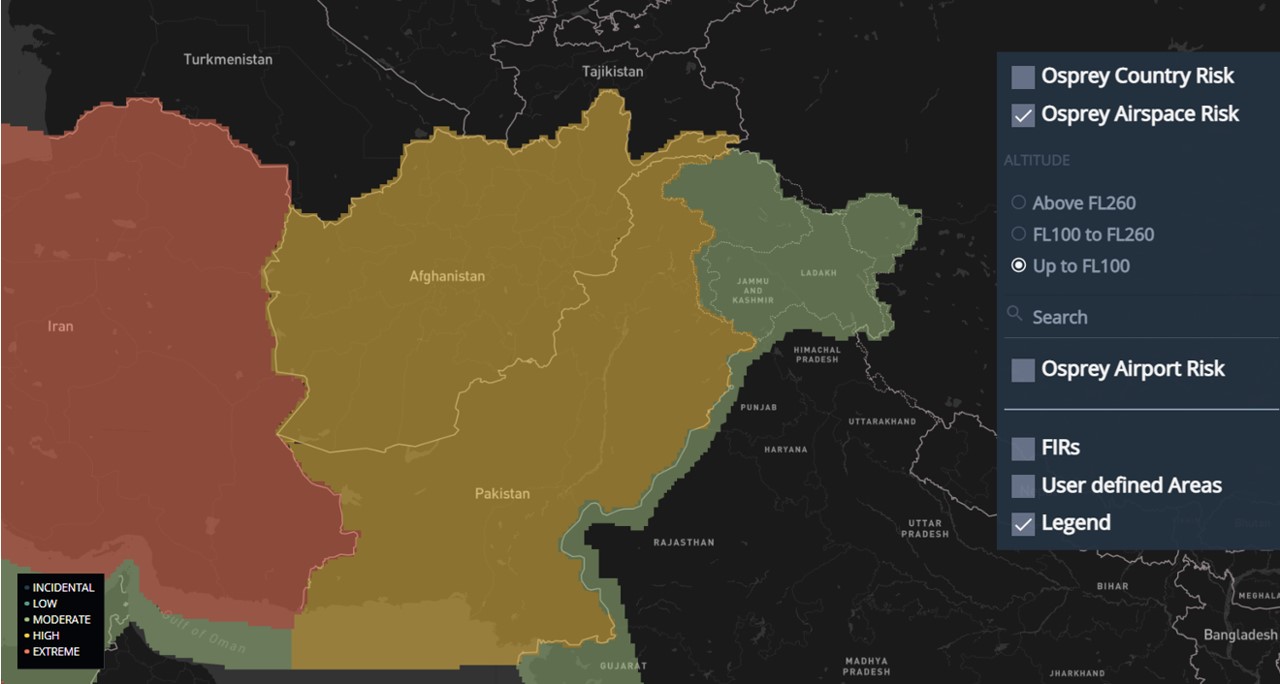

A NOTAM issued on 30 August states that due to security reasons Kabul ACC is released to military control; no ATC will be available and aircraft transiting through FIR Kabul (OAKX) will be flying in uncontrolled airspace at their own risk (OAKX A0672/21). Several leading aviation bodies have also issued advisories regarding Afghanistan:

- On 31 August, France reissued its NOTAM, valid through 26 September, requesting operators not enter FIR Kabul (OAKX), except for ATS route P500/G500 above FL260, superseding the current advice in its conflict zone AIC (LFFF F1360/21, France – AIC A 07/21);

- On 31 August, Germany issued a NOTAM prohibiting its operators from entering FIR Kabul (OAKX), superseding the current advice in its conflict zone AIC advising operators avoid flights below FL330 (EDGG B1199/21, Germany – AIC 10/21).

- On 30 August, the US FAA issued an updated NOTAM regarding Afghanistan restricting US aviation operators from conducting flights in FIR Kabul (OAKX) with the exception of ATS route P500/G500 (KICZ A0029/21);

- On 26 August, the UK issued a NOTAM advising its operators to defer conducting flights within FIR Kabul (OAKX) (EGTT V0021/21);

- On 20 August, Canada issued a NOTAM (CZYZ G1396/21) requesting operators avoid FIR Kabul (OAKX), replacing a previous NOTAM advising operators avoid flights below FL260;

- As of 16 August, ICAO had activated a Contingency Coordination Team (CCT) due to the situation in Afghanistan. This is standard protocol for managing such situations as the CCT combines the resources of ICAO in the regions involved, all affected states and Eurocontrol. On 17 August, Eurocontrol posted an update on Afghan airspace from EASA: https://www.public.nm.eurocontrol.int/PUBPORTAL/gateway/spec/

- Along these lines, IFALPA has issued a publication regarding the lack of ATC in FIR Kabul (OAKX): https://www.ifalpa.org/publications/library/update-ats-not-available-in-kabul-fir–3490

Analyst Comment

Afghan government ATC workers in the capital have reportedly abandoned their posts. Several leading carriers had already indicated that they would avoid overflight of Afghan airspace in the near term due to concerns over the continuity of ATC provision in FIR Kabul (OAKX). A Turkish and Qatari agreement with the Taliban for a presence after 31 August would likely aid in the provision of ATS service at Kabul Airport going forward, though this has yet to materialise. The NOTAM stating that FIR Kabul (OAKX) is now uncontrolled airspace represents a significant safety-of-flight concern, and rerouting of flights away from Afghan airspace is now a definitive operational constraint. Operators should remain prepared for a loss of access to FIR Kabul (OAKX) for the foreseeable future.

Taliban: Military Equipment & Air Bases

In addition to the civilian airports discusses above, the Taliban has taken control of Shindand Air Base (OASD/OAH) in Herat and Bagram Air Base (OAIX/OAI) in Parwan, as well as Helmand’s Camp Bastion (OAZI/OAZ) and Camp Dwyer (OADY/DWR). The Taliban has usurped a substantial amount of military equipment in the process of taking control of military installations, airports and airbases across Afghanistan. This includes military helicopters such as US-made UH-60 Black Hawks and MD-530s and Russian-made Mi-8s and Mi-17s. In addition, the Taliban has taken possession of US-made Scan Eagle military-grade drones and A-29 Super Tucano combat aircraft. The Taliban may have also taken over some military and civilian transport aircraft and civilian airliners at military installations, airports and airbases across Afghanistan.

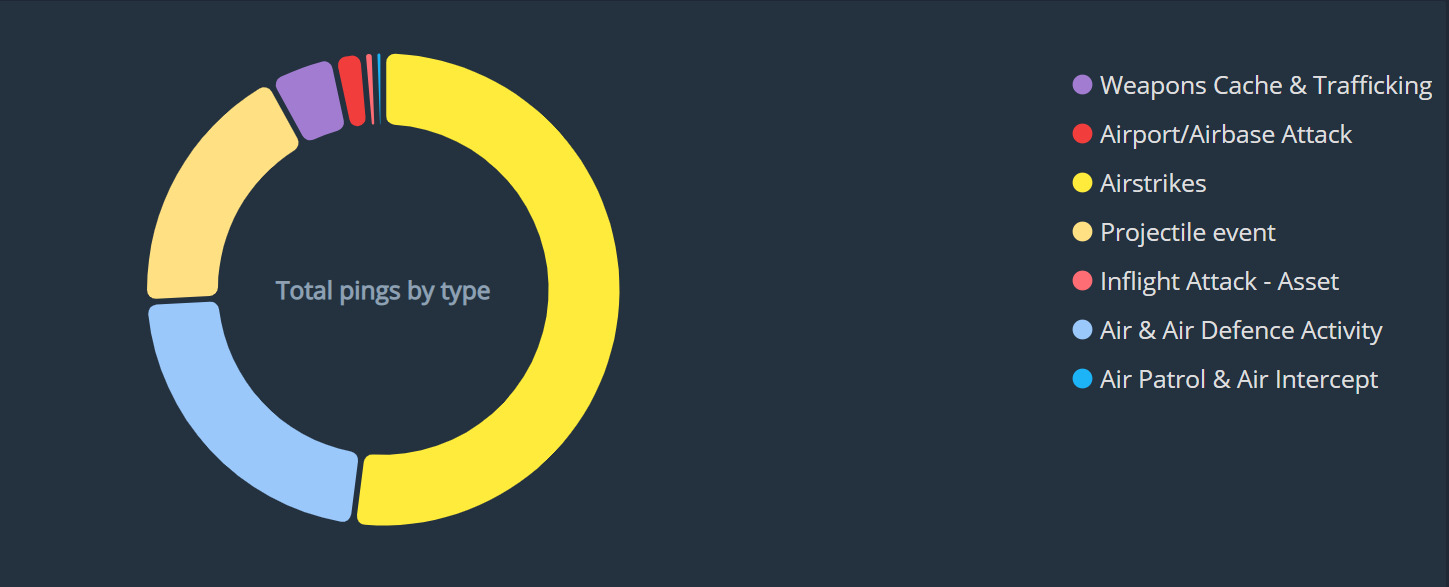

The Taliban likely gained control of large quantities of rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs), unguided anti-tank weapons (ATWs) and low-calibre anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) pieces, all capable below FL100. The Taliban may have also gained access to limited quantities of anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMS). Open-source intelligence reporting from late October 2017 indicates the Afghan Taliban claimed to have received HJ-8 ATGMs from weapons-trafficking sources in Pakistan.

The Taliban may also have gained access to small quantities of man-portable air-defence systems (MANPADS) stocks (i.e. Russian-made Strela-pattern) when overrunning military installations, airports and airbases across Afghanistan during August, though there is no publicly available confirmation of this. Reporting from May indicates that the Taliban remains in possession of at least a limited quantity of Chinese-made HN-5 MANPADS. The last publicly reported assessed MANPADS event over Afghanistan occurred in early October 2015, when a US military AC-130 gunship was unsuccessfully targeted by the Taliban while operating over Konduz province. Open-source intelligence reporting from late October 2017 indicates the Afghan Taliban claimed to have received Anza Mk-II MANPADS from weapons-trafficking sources in Pakistan.

Analyst Comment

While not all the air assets noted are operational, at least some appear to be, and the Taliban’s capability/intent with regards to operating them going forward is unclear at this time. Prior to its final withdrawal, the US military disabled 73 aircraft at Kabul Airport, and similar measures may have been taken by the Afghan Armed Forces prior to handing over airbases to the Taliban. Osprey assesses that the Taliban will face severe challenges with both operating and maintaining any air assets it has usurped in the medium-to-long term as it would be a significant logistical hurdle without external assistance.

Based on publicly available information, there are no indications of operational conventional surface-to-air missile systems capable above FL260 in Afghanistan, so that is not a concern at present. While the Taliban has likely accumulated a large quantity of light and guided weapons in the course of its territorial gains in recent months, they were already in possession of these types of arms – including MANPADS and ATGMs – before their takeover of the country. Despite the Taliban having access to these weapons, the withdrawal of foreign military forces from the country and the surrender of the Afghan army en masse indicates that armed clashes as well as air-supported security operations will likely decrease significantly in Afghanistan through the remainder of 2021. The expected significant decline in aerial operations in the country during that timeframe would decrease the likelihood of attempted surface-to-air fire engagements targeting military-grade air assets below FL260 and limit the potential for misidentification.

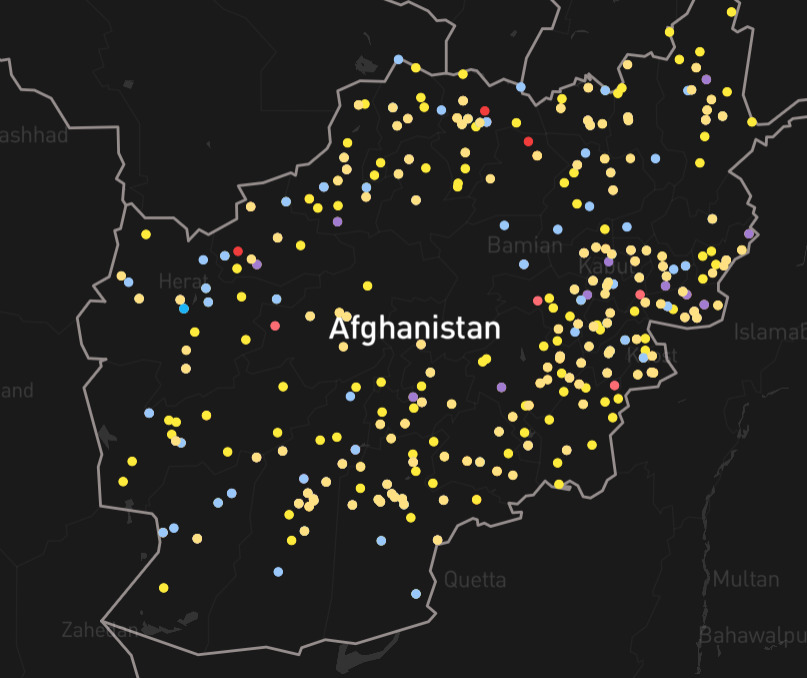

Threat: VNSA Groups in Afghanistan

There remains an enduring threat to aviation facilities in Afghanistan, also illustrated by previous incidents. On 26 August, an IS-KP attack involving one suicide bomber and additional assailants using small arms targeted crowds outside the Abbey Gate on the south side of Kabul Airport. The Pentagon has confirmed that at least 13 US military personnel died as a result of the attack, and media reporting indicates over 170 additional deaths occurred from the bombing. On 29 August, the US military reportedly conducted a drone strike in the PD-15 area of the Afghan capital against a vehicle carrying multiple IS-KP suicide bombers who were allegedly planning to attack Kabul Airport.

Two incidents highlight the realities of the enduring terrorism threat to aviation operations within Afghanistan: First, on 2 July, Afghanistan’s National Directorate of Security stated that it had thwarted an attack on a domestic flight from Herat Airport to Kabul Airport when an individual was prevented from boarding the aircraft with an improvised explosive device (IED) “skilfully” concealed within a musical instrument. Second, on 30 April, an IED attack reportedly occurred at a mosque located within the Bagram Air Base perimeter, targeting Afghan military personnel. The Deputy Police Chief of Parwan Province stated that the IED was placed in the ceiling of the mosque. No VNSA group has claimed responsibility for either incident, though IS-KP remains a potential perpetrator.

Since 2018, IS-KP has conducted rocket and mortar attacks on several aviation facilities in Afghanistan, including Bagram Air Base, Kabul Airport and Jalalabad Airport. On 30 August, IS-KP conducted a rocket attack targeting Kabul Airport; however, a US military counter-rocket, artillery & mortar (C-RAM) air-defence system shot down several incoming projectiles. Of note, the US military subsequently destroyed its C-RAM system at Kabul Airport prior to the final departure of its remaining forces on 30 August. On 12 December 2020, an IS-KP rocket attack involving over 10 projectiles targeted Kabul Airport, causing damage to two unoccupied commercial aircraft on a parking apron.

IS-KP and other VNSA groups remain active, predominantly in parts of eastern Afghanistan. These groups likely possess notable quantities of RPGs, unguided ATWs and low-calibre AAA capable below FL100. There is no publicly available information indicating IS-KP is in possession of MANPADS. The US military confirmed on 26 August that it does not assess that IS-KP is in possession of MANPADS. However, it remains possible the group may have access to such weapons due to their historical availability in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Reporting since 2020 indicates that the Taliban has made use of drones in attacks, reconnaissance operations and/or propaganda development in the following provinces: Konduz, Paktika, Wardak, Ghazni, Logar, Zabul, Paktia, Khost, Faryab, Balkh, Kandahar and Helmand. However, in 2021 the Taliban was reportedly able to effectively weaponise drones in Afghanistan and target air assets on the ground:

- On 15 January, the Taliban conducted a weaponised drone attack involving air-released improvised munitions targeting the Afghan Army’s 217th Corps headquarters in Konduz province, severely damaging a parked US-made MD-530 helicopter.

- On 10 July, the Taliban conducted a suspected weaponised drone attack targeting Konduz Airport, destroying at least one Afghan military US-made UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter parked at the installation.

- On 16 July, the Taliban reportedly conducted a suspected weaponised drone attack on Konduz Airport that allegedly resulted in the destruction of an Afghan military Black Hawk helicopter parked at the installation.

- IS-KP has also been linked to small commercial drone activity in Afghanistan in recent years. On 6 May 2020, Afghan security forces conducted a raid targeting an IS-KP cell in the capital Kabul and recovered a weapons cache containing mortars, RPGs and a small commercial quadcopter drone. An IS-KP cell was reportedly arrested in possession of a quadcopter drone, explosives and small arms in Kabul in early January 2018.

Analyst Comment

Poor provision of security through porous borders and an influx of weapons, including anti-aircraft systems, has facilitated a resurgence in VNSA activity in recent years in Afghanistan. The country has historically been a hub of VNSA activity and a key route for arms smuggling given its remoteness and anti-government sentiment due to the lack of economic opportunities. Throughout the country, large, relatively unpoliced areas are particularly vulnerable to security and terrorism threats due to instability and porous borders, which are exploited by VNSA groups..

Several US government reports from 2019-2020 noted that extremist groups continued to plan attacks targeting foreign and Afghan government interests in the country. However, in terms of targeting aviation-related entities, these tend to manifest themselves in IED attacks in the vicinity of airports, or indirect-fire and surface-to-air fire events below FL260 within the conflict zone environment. Plots to carry out on-board attacks against commercial aircraft are extremely rare. IS-KP will likely continue to sporadically target aviation-capable facilities in Afghanistan via indirect fire and possibly via suicide bombers or direct assaults using complex attacks through 2021.

Indirect-fire attacks via rockets, mortars or artillery against airports and air bases within the country pose an enduring threat to military and civil aviation air assets while on the ground in Afghanistan. IS-KP is assessed to have a variety of rockets, mortars, and potentially military-grade artillery pieces within their inventory. Aircraft on the ground at installations face a credible risk of being damaged due to indirect-fire attacks, particularly in eastern Afghanistan where IS-KP is most active. The Taliban face difficulty controlling the wide area surrounding most installations, creating a vulnerability that is difficult for operators to mitigate. The lack of a C-RAM system at Kabul Airport following the US military withdrawal also further increases the vulnerability of the Afghan capital.

The US president on 26 August indicated that military plans were being developed to strike IS-KP targets in response to the attack at Kabul Airport. In response to the suicide bombing, on 28 August, the US military announced it had conducted an airstrike against IS-KP attack planners in Nangarhar province, eastern Afghanistan. Additional aerial operations in the country by the US against IS-KP in the near term – should they occur – would increase the likelihood of attempted surface-to-air fire engagements by IS-KP targeting military-grade air assets below FL260 – particularly in eastern Afghanistan – as well as armed attacks against fortified installations with aviation infrastructure, as a means of retaliation against foreign interests. The threat of asymmetric targeting of armed forces’ aviation installations, airbases and airports along with military and civilian aircraft at low altitudes in the country in the medium term remains credible. Airports, airbases and air assets at low altitudes will remain vulnerable due to the high-impact nature of attacks against aviation targets.

The incidents above indicate a tactical shift by the Taliban to not only employ drones to film attacks for propaganda purposes and/or pre-attack reconnaissance, but now for weaponisation as a means of kinetic strike. Osprey analysis of multiple areas of armed conflict coupled with an in-depth examination of global terrorism trends indicates that drone use by militants for reconnaissance, propaganda development and weaponisation for attacks is steadily expanding. Drone use by VNSA groups inside areas of armed conflict highlights evolving tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) available as an inexpensive and effective means of terrorism and insurgency. These developments highlight the metastasised nature of global terrorism trends and the increasing number of TTPs available to militants seeking to use drone technology.

Threat: External Counterterrorism Concerns

Concerns continue to be raised regarding individuals posing a potential security threat – those on so-called ‘no-fly’ watchlists – getting onto evacuation flights out of Afghanistan. Several cases have been reported:

- On 24 August, media reporting citing unnamed US officials stated that one individual was suspected of “potential ties” to IS-KP, having been detected by screeners at Al Udeid Air Base (OTBH/XJD) in Qatar after arriving from Kabul. This has not been officially confirmed by the US government. The same reporting said “up to 100” evacuees had potential matches to US watchlists.

- On 23 August, the UK government confirmed one individual matching a name on the UK’s no-fly list was able to fly to Birmingham Airport (EGBB/BHX) in the UK on an evacuation flight. After investigation, the individual was not deemed to be a person of interest.

- Media reporting citing UK Border Force officials has stated that another individual on the UK no-fly list was on a flight to Frankfurt Airport (EDDF/FRA) in Germany, and four others were flagged at Kabul Airport.

- The French government said it evacuated an individual who admitted to having Taliban links as he had assisted with the evacuation from the French embassy in Kabul. The individual and four others close to him are now subject to “surveillance measures” in France.

While IS-KP is an Afghanistan-based IS affiliate, there is evidence it has been able to project itself beyond the country’s borders. In April 2019, German police arrested four suspected IS-linked individuals – all Tajik nationals – who were allegedly planning to carry out attacks against US military facilities in Germany, including air force bases; a fifth Tajik suspect was already in custody. German federal prosecutors alleged the cell was in contact with IS leadership figures in Syria and Afghanistan, from whom they had received instruction, and that one of those arrested was involved in fundraising and administering propaganda channels for IS-KP.

Analyst Comment

With regards to the no-fly list incidents, it is likely that further such cases have occurred – or individuals of concern have been flagged – among all nations that have carried out evacuation operations from Afghanistan, but not all will have been publicised. In response to the above incidents, the UK government has stated that its system is working as the individuals were flagged, albeit in two cases apparently only once further checks were made after they got on flights. This suggests that the security checks being carried out at Kabul Airport may not have been sufficient, potentially highlighting the pressured operational circumstances at the airport during the evacuation. However, it is not clear whether they were flagged but allowed to continue their journey; nor is it known what kind of security threat they may have posed – individuals can be placed on no-fly or other watchlists for various reasons, including terrorist-related activity as well as other criminality. Furthermore, as illustrated by the Birmingham individual and some previous no-fly list cases, matches with names and dates of birth can be flagged, but they may not actually be the person of interest, or further investigation can establish that they are no longer deemed a security concern. There has been no suggestion that any of the individuals posed an actual threat to the flights. However, the situation highlights enduring concerns among governments and air carriers that extremists continue to seek to travel from theatres of conflict – including by using fraudulent documentation – to return home or, in some cases, to carry out attacks in destination countries.

While there are no current indications that the Taliban will itself seek to project any threat – including to aviation – outside Afghanistan, concerns have already been expressed by Western and other governments that the Taliban, knowingly or otherwise, will provide a safe operating environment for terrorist groups. Under the previous Taliban regime, the group provided shelter for al-Qaeda (AQ), including its leadership under Osama Bin Laden, enabling it to plan and execute terrorist attacks around the world, including the 9/11 attacks in 2001. While it is unclear what level of cooperation – if any – may ensue between the Taliban and the current AQ leadership, it remains possible that the organisation, or other extremist groups, may be able to take advantage of any freedom of operation in an ungoverned space, as the Taliban is unlikely to be able to exert full control over every part of the country. AQ has long held the terrorist pedigree for targeting aviation, and following 9/11, AQ and its regional affiliates attempted a series of attacks using increasingly sophisticated concealed improvised explosive devices (IEDs) designed to defeat aviation security measures. In 2014, limits and checks on personal electronic devices like mobile phones, tablets and laptops were introduced on commercial flights worldwide, reportedly in response to intelligence indicating that the so-called Khorasan Group, a collective of AQ veterans in Syria (and unconnected to IS-KP), was plotting to attack aviation using explosives concealed in such devices. This group was able to develop the plot while operating in the permissive environment created by the Syrian civil war.

Similarly, while ideologically opposed to the Taliban, it is possible that IS-KP may be able to thrive in such a permissive environment. This is of particular concern given the wider Islamic State (IS) group was able to successfully establish an external operations capability, including developing techniques, planning attacks and deploying operatives overseas, while it held considerable amounts of territory in Syria and Iraq during the period 2014-2017. Of particular concern to aviation, the 2017 Sydney Airport bomb plot – in which the would-be attackers aborted an attempt to take an IED concealed in a meat grinder on an airliner in July 2017 – was planned and directed by IS operatives based in Syria. The group has continued to inspire and influence followers abroad to carry out terrorist attacks, and IS-KP itself has shown it is capable of providing support and direction to sympathisers overseas, as demonstrated by the 2020 arrests in Germany mentioned above. Furthermore, dependent on how the situation in the country develops, Afghanistan may become an attractive destination for extremists seeking to join any such groups. Emboldened and encouraged by perceived successes, terrorist groups – including AQ and IS and their affiliates, including IS-KP – are likely to continue to project the threat they pose abroad and may look to target commercial aviation in future through developing ever-more sophisticated methods of attack.

Conclusion

The US, UK, Germany and France, along with a number of other countries, have stated that the Taliban have provided assurances that their respective nationals and Afghan refugees with proper foreign travel documentation will be allowed to depart the country either via land border crossings or airports, once operational. However, neither the international community nor the Taliban have provided specific details on how such efforts will proceed, including at airports. We assess that a heightened potential remains for armed clashes between the Taliban and IS-KP or other VNSA factions in the country to persist through the remainder of 2021 or until a comprehensive political and military agreement is reached between within Afghanistan.

We also assess that a heightened potential remains for unsafe air activity to occur over Afghan airspace through 2021 as FIR Kabul (OAKX) is expected to remain uncontrolled for the foreseeable. While the likelihood of a catastrophic event is low, uncontrolled civilian and military air activity in Afghan airspace may result in civilian and military aircraft not always using transponders, there will be a lack of ATC radio contact and/or operators may not file proper flight plans. As a precaution, conduct operational risk-based identification of divert and alternate airports for flight schedules with planned stops at aerodromes in the country or with overflight of the airspace. Operators are advised to ensure flight plans are correctly filed, attain proper special approvals for flight operations to sensitive locations and obtain relevant overflight permits prior to departure.

Aviation operators should monitor airport/airspace-specific notices, bulletins, circulars, advisories, prohibitions and restrictions prior to departure to avoid flight schedule disruption. Several aviation authorities – including the US, the UK, EASA, France, Germany and Canada – have issued advice and direction to operators in the past year regarding flights within FIR Kabul (OAKX).

Osprey assesses Afghanistan to be a high-risk airspace environment at all altitudes.

Afghan airspace risk mitigation recommendations:

- Flights below FL260 not advised; essential flights over FL260 via measures below:

- Defer diverting from flight plan with the exception of life-threatening situations;

- Security and operational risk-based identification of pre-planned divert airports;

- Reliable and redundant communications with an established communications plan;

- Fully-coordinated and robust emergency response plan supplemented by asset tracking.